A friend's agent advised her to write a 'reading-group' book, because 'that's what publishers are interested in'. I've noticed that some books are now so targeted that they include 'discussion questions' as if they were A-Level set texts. It made me wonder about makes a good reading group book and I applied the question to two examples that came up last week.

I'm enrolled in four groups, all meeing in local libraries. In lean times, this is fine, but when I have a pile of own-choice books, not to mention those I've agreed to review, it's a bit of a challenge.

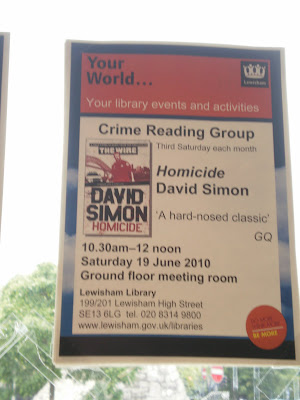

No wonder I mix up venues. For Thursday's discussion of The Quiet American, no problem; the librarian at Blackheath Village sends reminders. But I turned up at Manor House Library on Saturday morning only to be redirected to Lewisham High Street.

Irene Nemirovsky's Fire in the Blood , written in the 1940s, is a recent publication, discovered only years after the writer died at Auschwitz. Her husband sent their daughters to safety shortly before his own arrest. They carried their mother's papers in a suitcase. She was already author of a best-seller, David Golder, which I haven't read but which was made into a successul film.

I did read Suite Francaise , for one of the groups, last year. In it, Nemirovsky was unflattering about members of the French middle classes fleeing Paris just before the Nazi invasion. Fire in the Blood similarly condemns hypocrisy and avarice in village based on one where the author lived. Young women are married off to old men and take young lovers; such activities and and more sinister ones are ignored. The narrator, an elderly curmudgeon cum prodigal son, hides his own murky secrets.

One of the readers thought the narrator was too unpleasant, despite his 'fire in the blood' philosophy, excusing youthful folly and worse ; another found the author too manipulative. Accustomed to crime fiction and its surprises I didn't mind the 'unreliable' narrator, but thought establising the claustrophobic milieu delayed the onset of the narrative. Two members found interesting parallels with their own experiences of respective Spanish and Scottish villages.

Graham Green's The Quiet American met a more sympathetic reception from older readers at Blackheath Library on Thursday. The main protagonist, anti-hero journalist Fowler is a variation on Greene's archetypal expat, morally and spiritually compromised. This world-weary fifty-something opium addict is covering the French war in Vietnam while vying with a young American for possession of a local beauty. Discussion centred around the historical background and colonialism.

Good 'reading group books', I conclude, are books that have important themes, such as justice, hyocrisy, greed, history, love and war, plus a strong narrative, an unusual setting and remarkable characters. In other words, ingredients that good books had even before the recent proliferation of reading groups.